‘Do you want to see a blackbuck?’ asked Thana Ram Bishnoi, with a slight smile.

We were sitting on a charpoy in his courtyard, getting acquainted. We readily agreed.

The sun had turned softer and the air cooler; soon it would be dusk. We strapped on our shoes as Thana Ram picked up his stick and we set off for the vast, dry land beyond his house, dotted with shrubs and bare trees. We left the last couple of houses behind us walking through the fields, towards the animals we could see in the distance. We inched ahead slowly; sudden movement would drive them further away, and our host was cautious. There was no sound except for the buzzing of flies and a slight breeze that whistled and deposited fine desert sand everywhere. In this desolate place, I half expected John Wayne to saunter up with one hand casually resting on his pistol, asking us to explain ourselves. I wasn’t in a Hollywood western though, but on the outskirts of the village of Pheench, not easily found on the map, to spend a couple of days at the home of a Bishnoi family.

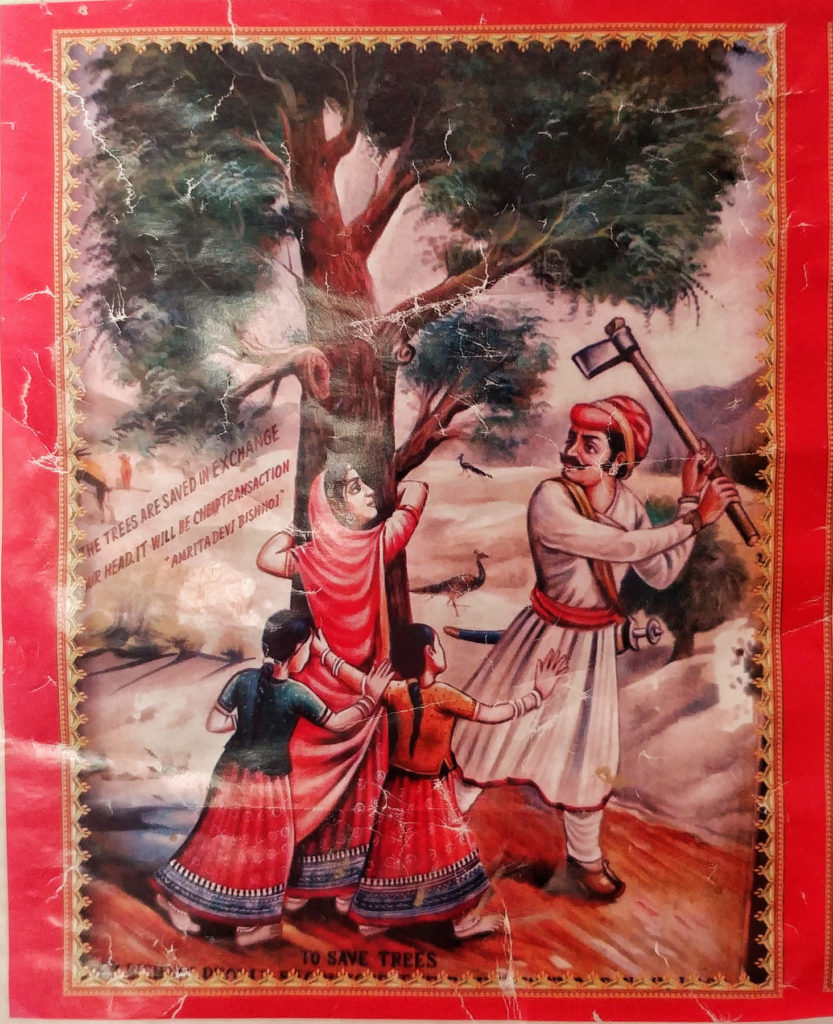

One of the earliest known communities who believe in the sanctity of all life, the Bishnois have fiercely protected nature and animals around them, for over 500 years, allowing them to survive in the harsh Thar desert. In modern times, they have also had a pivotal role in safeguarding the wildlife of the region and were thrust into the limelight during the infamous incident surrounding Salman Khan and the poaching of blackbuck in the late 1990s. But their commitment to nature dates much further back to the time of Maharaja Abhay Singh of Jodhpur, whose men were sent to cut the Khejri tree from a Bishnoi village, to be used as building material for a palace. The Bishnois, who consider the Khejri sacred, protested; they hugged the trees, refusing to allow their felling. For this impudence, it is said they paid with their lives, and were cut down along with the trees — 359 of them massacred before the issue was brought to the attention of the King.

This incident from 1730 AD is narrated with sadness and pride by everyone we met, an important landmark in Bishnoi history. Followers of the faith propounded by sage Jambeshwar in the mid-1400s who had a vision of people living in harmony with nature or risk peril, the community follows the 29 principles that he set down: ‘Bish’ meaning 20 and ‘Noi’ nine, in Marwari. These included not felling trees, having a holistic and compassionate world-view, (following) hygienic living and (keeping) a clear conscience. It is these principles that have kept the community together for centuries, safeguarding all life around them; they even bury their dead so as to not waste trees for the funeral pyre.

We’d reached as close as we could and Thana Ram motioned for us to stop. A short distance away, we could see two males with their black upper sides and white undersides, and several younger faun blackbucks, having a quiet evening frolic. It was a beautiful sight, a slowly dipping sun in the background highlighting their wavy antlers. After some quiet observation, happy with what we’d seen, we headed back to the house. Thana Ram pointed out the small watering ponds the villagers have built for the blackbuck and other animals. Water is scarce here, as in most of western Rajasthan, with even groundwater salty and undrinkable. There is one well that serves sweet water and the government has only in the last few years brought piped water to their village. The community in this region manage only one crop-sowing a year and are frugal, yet manage to still save some resources for the wildlife.

Our stay at Thana Ram’s home, in a bid to understand and experience the Bishnoi way of life, was enlightening to say the least. Later, I (Ambika) sat with Dulli, the daughter-in-law of the house, as she made dinner in the indoor kitchen, using only cowdung, dead wood and shrubs for the cooking fire. As is dictated, she ensured that there are no insects on the wood before putting them in the fire; she cooked a dish with tomatoes, chillies and leftover malai from the days’ milk, churning out hot, thick rotis slathered in homemade ghee at amazing speed.

She hasn’t studied beyond Class Eight. While her father and brothers tried to insist she went to school, she realised it wasn’t for her and chose to learn how to sew. She wants to sell the clothes she makes, once her husband (Thana Ram’s son) finishes university. Her face is covered, as is the custom when her in-laws are around. But when we are alone, she uncovers her head and shows me her lovely jewellery: the nose ring and trademark round maang tikka. I was asked the inevitable question of why I don’t wear any obvious signs of marriage — nothing on my forehead, toes or neck — and the lack of children, and we talked a little about the availability of choice. We chatted, two women who have vastly different lives, yet find much to talk about: common threads that bind women around the country.

We were quite the anomaly in a village that doesn’t see many outsiders let alone tourists and the next morning we walked through the village, house hopping and drinking copious amounts of chai. Extremely hospital people, not unlike many other parts of India, the Bishnoi will first serve you water and invite you home for tea before anything else, even if you have only asked them for directions. They were curious about us, most travellers do half-day visits to other Bishnoi villages closer to Jodhpur and were pleased that we were there to understand and learn their way of life. Conversations revealed more about their lives and fierce loyalty to nature as dictated by their guru, where the spirit of conservation has been deeply ingrained into their lives. They might still live in relative poverty in these parts with traditional values when it comes to equality, but there is much we can learn from this resilient community, the original environmental warriors.

A version of this story first appeared in Firstpost as part of the #FTravellers series on reDiscovering Rajasthan